Government 2: Oversight

Oversight

Contents

The need to guard the guardians has been a slow concept to develop in human history. Rulers had God on their side, or were gods, and it’s only in the last few centuries that there’s been even a concept of checks and balances. But, as usual, the powerful find workarounds and we’re back to the point where “you can’t fight City Hall” is considered a cliché.

In a sustainable system, that is, in a fair one, that feeling can’t exist. If it does, the system won’t be sustainable. Without effective oversight of the government, a sustainable system won’t happen.

Real oversight depends on the independence and intelligence of the overseers, with the first factor apparently much more important than the second. The financial meltdown, the false evidence for the US to start a war in Iraq, the astonishing loss of consumer control over purchased digital products: these all depend(ed) on cozy relationships among the powers-that-be. Those powerful people are, if anything, smarter than average. So the first requirement of oversight is that it has to be distributed, not concentrated among an elite. It should, furthermore, stay distributed and avoid creeping concentration from re-emerging. This is where current methods fall down. Elections happen too rarely and voters can be manipulated for the short periods necessary. Lawsuits take too much time and money to be more than a rearguard action. Our current feedback loops are far too long to work consistently.

There are a few pointers showing what will work. Although no current government has effective oversight unless officials cooperate (which suggests the system relies more on the hope of honesty than a requirement for it) many governments do employ elements of oversight. Some things clearly work better than others.

First is that transparency prevents the worst behavior, or at least enables citizens to mobilize against it. Full scale looting of public money and dreadful decisions taken for self-serving ends require secrecy.

Second is that elections do cause politicians to sit up and take notice. Unfortunately, when the elections occur on a schedule, the politicians only pay attention on that schedule. One essential change is a framework to call elections — in the system described here that would be recall elections — at any time.

Third, and now we’re already in largely untested territory, is the need for finer-grained feedback. It’s essential to have ways of communicating dissatisfaction and implementing the necessary corrections which are both effortless and scalable. An escalating system of complaints might be a solution.

Fourth, in the case of plain old criminal wrongdoing, there need to be criminal proceedings, as there officially are now.

Fifth is the need for oversight to have its own checks and balances. Government is a tensegrity structure, not a pyramid. Officials need to have ways of responding to complaints. And the system of oversight itself must be overseen.

Who does the overseeing is as important as how. Distributed — in other words, citizen — oversight is the essential part, but citizens have other things to do besides track officials. There also need to be professional auditors whose task is the day-to-day minutia of oversight. They keep tabs on all the data provided by transparency, take appropriate actions as needed, and alert the public to major developing problems that are overlooked. This is another area where professionals are needed for the boring or technical details and the general public is needed to ensure independence and functional feedback.

So, starting with transparency, the first thing to note is what it isn’t. It is not a data dump. It is not an exercise in hiding some data under a mountain of other data. It does not mean keeping every record for the sake of theater. It doesn’t mean stifling interactions by perching the Recording Angel on everyone’s shoulders.

Transparency means the optimum data for the purpose of promoting honesty in government. Information not relevant to that purpose is just noise that masks the signal. However, as always when an optimum is required, the difficulty is finding the right balance. If the right to know is defined too narrowly, there’s the risk of oversight failure. If it’s defined too broadly, official interactions may be stifled for nothing or privacy may be recklessly invaded. Organizations such as Transparency International have considerable data on how to approach the optimal level. The more governments that have a commitment to providing clear and honest data, the more we’d learn about how to achieve the most useful transparency with the least intrusion and effort.

What we know so far is that financial data and records of contacts and meetings provide two of the clearest windows on what officials (also non-governmental ones) are up to. Financial data in the hands of amateurs, however, can be hard to understand, or boring, or vulnerable to attitudes that have nothing to do with the matter at hand. For instance, accountants have the concept that tracking amounts smaller than what it costs to track them are not worth following. Amateurs, on the other hand, will notice a trail of gratuitous donuts but feel too bored to follow statements of current income as present value of net future cash flows. The fact that the statement is Enron’s means nothing beforehand. It is important to ignore the easy distractions of small stuff and to notice the big stuff, especially when it’s so large it seems to be nothing but the background.

There were plenty of auditors involved in the Enron fiasco who knew better, of course. That wasn’t a simple matter of amateurs distracted by ignorance. However, the auditors received vast sums of money from the company, which simply underlines the need for true independence in oversight, including independence from membership in similar networks. Real transparency would have made the necessary information available to anyone, and would have prevented both the disaster and the pre-disaster profits, some of which flowed to the very people supposedly in oversight … which is why oversight wasn’t applied in time.

Records of meetings and contacts are another important source of data about what officials are doing, but that raises other problematic issues. People need to feel able to speak candidly. After all, the whole point is to promote honesty, not to generate ever newer layers of speaking in code. A soft focus is needed initially, followed by full disclosure at some point. Maybe that could be achieved by a combination of contemporary summaries of salient points and some years’ delay on the full record. The interval should be short enough to ensure that if it turns out the truth was shaded in the summaries, corrective action and eventual retribution will still be relevant. The interval would probably need to vary for different types of activity — very short for the Office of Elections, longer perhaps for sensitive diplomatic negotiations between countries.

Presentation of information is a very important aspect of transparency, although often overlooked. This may be due to the difficulty of getting any accountability at all from current governments. We’re so grateful to get anything, we don’t protest the indigestible lumps. Governments that actually served the people would present information in a way that allows easy comprehension of the overall picture. Data provided to the public need to be organized, easily searchable, and easy to use for rank amateurs as well as providing deeper layers with denser data for professionals. If these ideas were being applied in a society without many computers, public libraries and educational institutions would be repositories for copies of the materials.

A related point is that useful transparency has a great deal to do with plain old simplicity. The recordkeeping burden on officials should be made as simple and automatic as possible. In an electronic world, for instance, any financial transactions could be routed to the audit arm of government automatically and receive a first pass computer audit. Some simplicity should flow naturally from requiring only information relevant to doing the job honestly, rather than all information.

Information relevant to other purposes, such as satisfying curiosity, has nothing to do with transparency. Or, to put it another way, the public’s right to know has limits. An official’s sex life, for instance, unless it affects his or her job, is not something that needs to be detailed for the sake of transparency, no matter how much fun it is. Officials, like everyone else, do have a right to privacy on any matter that is not public business.

The professional audit arm of the government would have the job of examining all departments. The General Accounting Office fulfills some of that function in the US now, but it serves Congress primarily. In the system I’m thinking about, it would serve the citizenry with publication of data and its own summaries and reviews. It would also have the power to initiate recalls or criminal proceedings, as needed. (More on enforcement in a moment.)

A professional audit agency doesn’t provide enough oversight, by itself, because of people’s tendency to grow too comfortable with colleagues. Citizens’ ability to take action would counteract the professionals’ desire to avoid friction and ignore problems. But citizen oversight, by itself, is also insufficient. Its main function is as a backstop in case the professionals aren’t doing their jobs. The day to day aspects, the “boring” aspects of oversight need to be in the hands of people paid to pay attention.

Feedback is the next big component of oversight, after transparency. The sternest form of feedback is recall elections, but in the interests of preventing problems while they are still small, a system that aims for stability should have many and very easy ways to provide feedback.

The easiest way to give feedback is to complain. That route should be developed into an effective instrument regarding any aspect of government, whether it’s specific people, paperwork, or practices. Complaints could address any annoyance, whether it’s a form asking for redundant information or it’s the head of the global Department of Transportation not doing his or her job coordinating intercontinental flights. Anyone who worked for a tax-funded salary, from janitors to judges, could be the subject of a complaint.

It’s simple enough to set up a complaints box, whether physical or electronic, but effectiveness depends on three more factors. The first two are responsibility and an absence of repercussions. People have to be able to complain without fear of retribution. On the other hand, complaints have to be genuine in all senses of the word. They have to come from a specific individual, refer to a specific situation, and be the only reference by that person to that problem. Anonymity is a good way to prevent fear of retribution. Responsibility is necessary to make sure complaints are genuine. Somehow, those two conflicting factors must be balanced at an optimum that allows the most genuine complaints to get through. Possibly a two-tiered system could offer a solution: one tier would be anonymous with some safeguards against frivolous action, and one not anonymous (but with bulletproof confidentiality) that could be more heavily weighted.

The third factor is that the complaints must actually be acted upon. That means sufficient staffing and funding at the audit office to process them and enforce changes. Since effective feedback is crucial to good government, staffing of that office is no more optional than an adequate police force or court system. It needs to be very near the front of the government funding line to get the money determined by a budget office as its due. (The budget office itself would have its funding level determined by another entity, of course.)

It’s to be expected that the thankless jobs of officials will generate some background level of complaints. Complaints below that level, which can be estimated from studies of client satisfaction across comparable institutions, wouldn’t lead to action by others, such as officials in the audit agency. An intelligent official would note any patterns in those complaints and make adjustments as needed. If they felt the complaints were off the mark, they might even file a note to that effect with the audit agency. The fact that they were paying attention would count in their favor if the level of complaints rose. But until they rose, the complaints wouldn’t receive outside action.

In setting that baseline level, the idea would be to err on the low side, since expressed complaints are likely indicative of a larger number of people who were bothered but said nothing. The level also should not be the same for all grades. People are likelier to complain about low level workers than managers whom they don’t see.

Once complaints rise above what might be called the standard background, action should be automatically triggered. Some form of automatic trigger is an important safeguard. One of the weakest points in all feedback systems is that those with the power to ignore them, do so. That weakness needs to be prevented before it can happen. The actions triggered could start with a public warning, thus alerting watchdog groups to the problem as well. The next step could be a deadline for investigation by the audit office (or the auditors of the audit office, when needed). If the volume of complaints was enormous, then there’s a systemic failure somewhere. Therefore, as a last resort, some very high number of genuine complaints should automatically trigger dismissal, unelection, or repeal of a procedure. Transparency means that the volume of complaints and their subject is known to everyone, so when that point was reached would not be a secret.

I know that in the current environment of protected officialdom, the feedback system outlined sounds draconian. The fear might be that nobody would survive. That’s not the intent. If that’s the effect, then some other, more well-tuned system of feedback is needed. But whatever it’s form, an effective system that’s actually capable of changing official behavior and altering policies is essential. In a system that worked, there would be few complaints, so they’d rarely reach the point of triggering automatic action. In the unattainable ideal, the selection process for officials would be so good that the complaints office would have nothing to do.

I’ve already touched on recall elections, but I’ll repeat briefly. The recall process can be initiated either by some form of populist action, such as a petition, or by the government’s audit arm. After a successful recall, an official should be ineligible for public service for some period of time long enough to demonstrate that they’ve learned from their mistakes. They’d be starting at the lowest rung, since the assumption has to be that they need to prove themselves again.

The fourth aspect of oversight, punishment for crimes, corruption, or gross mismanagement by officials, is currently handled correctly in theory, but it needs much stricter application in practice. The greater the power of the people involved, the more it’s become customary, at least in the U.S., to let bygones be bygones after a mere resignation. It’s as if one could rob a grocery store and avoid prosecution by saying, “Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it.” Worse yet, the response to criminal officials is actually less adequate than it would be to treat shoplifters that way. The state sets the tone for all of society, so crimes committed by representatives of the state do more damage. So there must be real penalties for any kind of malfeasance in office. If there has been financial damage, it should be reimbursed first out of the official’s assets. Nor should there be any statute of limitations on negligence or problems generated by officials. They are hired and paid the big money to pay attention. If they don’t, they must not escape the consequences merely because people are so used to letting government officials get away with everything.

So far, my focus has been on ways of controlling officials, and that is the larger side of the problem. But, that said, officials do need ways of contesting overactive oversight, downright harassment, or unjustified recalls or prosecutions. The point of draconian oversight — draconian from our perspective that teflon officials are normal — is to have public servants who live up to their name. They must serve the public.

On the other hand, they’re an odd sort of servant because a significant part of their job is doing things for the public good which the public usually doesn’t like very much at the time. (If that weren’t true, there’d be no need for officials to do them. They’d get done without help.) So, there are two reasons why officials must be protected from capricious oversight. One is that servants have rights. Two is that they have to be able to take necessary unpopular steps without fear of reprisals. The public, after all, is as capable of abusing power as the individuals it’s composed of.

Complaints are the earliest point where an official could disagree with the public’s assessment. If the complaints are caused by a necessary but unpopular policy, the official needs to make clear why it’s necessary, and why something easier won’t do. Complaints happen over time, so if they’re a rising tide, that’s not something that can come as a surprise to the responsible party. The official’s justifications would become part of the record. When complaints reach a high enough level to be grounds for unelection or dismissal, and if the official is convinced that a decisive proportion of the complaints is unwarranted, they could ask for independent review. (An example of possible specifics is given below.)

However, after repeated cases that go against a complainant, those individuals should no longer have standing to bring future cases of that type. A case that went against an official would result in recall or firing, so repeated cases wouldn’t arise.

The audit arm of the government is another source of oversight that an official could disagree with. The ability to respond to its charges would be built into the system. If the responses passed muster, the case would be closed. If not, there could be appeals to a review board, and eventually the legal system. As in the example box, I’d see this as a process with limits.

Recalls are the most far-reaching form of oversight, and the ability to contest them the most dangerous to the health of the system. Contesting a recall should be a last resort and something that’s applied only in exceptional cases. Normally, if an official felt a recall was unjustified, they should make that case during the unelection and leave the decision to voters. However, for the exceptional case, officials could contest a recall if they had a clear, fact-based justification for why it had no valid basis. It would then go to reviewers or a legal panel with the necessary specialized expertise, chosen by the opposing sides as discussed earlier.

The biggest difference between those reviewers and others is that potential conflicts of interest would have to be minutely scrutinized. More nebulous loyalties should be considered as well in this case. The tendency to excuse the behavior of colleagues is very strong and it’s one of the biggest problems with oversight of government by government. As with any process involving a balance of rights, ensuring the independence of the arbiters is essential.

To provide an additional dose of independence, a second review track could be composed of a more diffuse pool of people with less but still adequate expertise, along the same lines as selectors who determine the eligibility of candidates for office. A matter as serious as contesting a recall should use both tracks at once, and be resolved in favor of the official only if both agreed.

As I’ve done before, I’ve provided some specific ideas about implementation not necessarily because those are good ways to do it, but mainly to illustrate my meaning. Whatever method is applied, the goal is to ensure the right of public servants to defend themselves against injustice, just like anyone else, and to prevent that from becoming an injustice itself.

Because of the potentially far-reaching consequences of contesting recalls, overuse absolutely must be prevented. If it was the considered opinion of most reviewers involved that an official who lost a bid to prevent a recall did not have grounds to contest in the first place, then that attempt should be considered frivolous. One such mistake seems like an ample allowance.

A structural weakness of oversight by the public is that officials have training, expertise, and familiarity with the system. That gives them the advantage in a contest with a diffuse group of citizens. An official’s ingroup advantage may be smaller against an arm of the government tasked with oversight, but that’s not the issue. The important point is that citizen action is the oversight of last resort so it sets the boundary conditions which must not fail. Since officials have the upper hand in the last-resort situation, it is right to err on the side of protecting oversight against the official’s ability to contest it. Officials must have that option, but it can’t be allowed to develop into something that stifles oversight. It’s another balance between conflicting rights. It may be the most critical balance to the sustainability of a fair system, since that can’t survive without honest and effective government.

Regulation

Contents

The government’s regulatory functions flow directly from its monopoly on force. What those functions should be depend on the government’s purpose which, in the case being discussed here, is to ensure fairness. People will always strive to gain advantage, and the regulatory aspects of government must channel that into fair competition and away from immunity to the rules that apply to others.

In an ideal world, the regulatory function would scarcely be felt. The rules would be so well tuned that their effects would be self-regulating, just as a heater thermostat is a set-it-and-forget-it device. More complex systems than furnaces aren’t likely to achieve this ideal any time soon, but I mention it to show what I see as the goal of regulation. Like the rest of government, when it’s working properly, one would hardly know it was there.

However, it is regulation that can achieve this zen-like state, not deregulation. This is true even at the simplest levels. A furnace with no thermostat cannot provide a comfortable temperature. In more complex human systems, deregulation is advocated by those powerful enough to take advantage of weaker actors. (Or those who’d like to think they’re that powerful.) It can be an even bigger tool for exploitation than bad regulations. The vital point is that results expose motives regardless of rationalizations. If regulation, or deregulation, promotes concentrations of power or takes control away from individuals, then it’s being used as a tool for special interests and not in the service of a level playing field.

Current discussions of regulations tend to center on environmental or protectionist issues, but that’s because those are rather new, at least as global phenomena. In other respects, regulations are so familiar and obviously essential that most people don’t think of them as regulations at all. Remembering some of them points up how useful this function of government is. Weights and measures have been regulated by governments for thousands of years, and that has always been critical for commerce. Coins and money are a special instance of uniform measures — of value in this case — and even more obviously essential to commerce. The validity of any measure would be lost if it could be diddled to favor an interested party. Impartiality is essential for the wealth-producing effects to operate. That is so clear to everyone at this point that cheating on weights and measures is considered pathetic as well as criminal. And yet, the equally great value of fairness-preserving regulation in other areas generally needs to be explained.

Maintaining a level field is a primary government function, so undue market power is one area that needs attention. The topic overlaps with the discussion about competition and monopolies under Capital in the Money and Work chapter, but it is also an important example of regulation that can be applied only by a government, so I’ll discuss it briefly here as well.

Logically, monopolies shouldn’t exist because there ought to be a natural counterweight. They’re famous for introducing pricing and management inefficiencies that ought to leave plenty of room for competitors. But, people being what they are, market power is used to choke off any competition which could reduce it. The natural counterweight can’t operate, and only forces outside the system, such as government regulations, can halt that process.

One point I’ve tried to make repeatedly is that fairness is not only a nice principle. Its practical effects are to provide stability and wealth. That is no less true in the case of preventing unbalanced market power. Imbalance leads to chaotic consequences during the inevitable readjustment. Having enough market power to tilt the field is not only unfair and not only expensive. It’s also unstable, with all the social disruption that implies. Recognition of that fact has led to the establishment of antitrust laws, but they tend to be applied long after economic power is already concentrated. They assume that the problem is one hundred percent control.

The real evidence of an imbalance is price-setting power. When a business or an industry can charge wildly in excess of their costs, that’s evidence of a market failure and the need for some form of regulation. I’ll call entities who are able to dictate prices “monopolies” for the purposes of discussion, even though they have only a controlling market share, not necessarily one hundred percent of it.

Some monopolies are well understood by now. The classical ones involve massive costs for plants or equipment and very small costs to serve additional customers. Railroads are one example. The initial costs are high enough to prevent new startups from providing competition. Equally classic are natural monopolies where one supplier can do a better job than multiple competing ones. Utilities such as water and power are the usual examples. There’d be no money saved if householders had water mains from three separate companies who competed to supply cheap water. The duplicated infrastructure costs would swamp any theoretical savings.

So far, so good. The need for regulated utilities is well understood. Regulated transport is a bit iffier. The need for a state to handle the roads is accepted, even among the free market religionists in the US, but the need for state regulation and coordination of transport in general is less widely recognized. The free marketeers here can be puzzled about why it takes a week to move things from Coast A to Coast B using the crazy uncoordinated patchwork of private railroads. But, on the whole, the need to enforce limits on pricing power, the need for standards and for coordination is known, if not always well implemented.

The same need for standards, coordination and limits on pricing holds with all other monopolies, too, but this isn’t always grasped, especially in newer technologies. Money is not the only startup cost that can form a barrier to entry. An information industry is a recent phenomenon that started with the printing press and has begun exponential growth after the computer. The main “capital cost” is not equipment but the willingness of people to learn new habits.

Imagine, for instance, that Gutenberg had a lock on printing from left to right. All later presses would have had to convince people to read right to left just so they could get the same book but not printed by Gutenberg. Good luck with that. Similarly with the qwerty keyboard. People learned to use it, it turned out to be a bad layout from the standpoint of fingers, and we’re still using it over a hundred years later. Only one cohort of people would have to take the time to learn a new layout, and that just doesn’t happen. If there had been a modern DMCA-style copyright on that layout, there’d still be nobody making keyboards but Remington.

History shows that people simply won’t repeat a learning curve without huge inducements. And so it also has dozens of examples of companies which had the advantage of being over the learning curve and thus had a natural monopoly as solid as owning the only gold mine. Any monopoly needs regulation. If it works best as a monopoly, then it has to become a regulated utility. If it’s important enough, it may need to be government run to ensure adequate transparency and responsiveness to the users. If it doesn’t need to be a monopoly, then it’s up to regulation to ensure that the learning curve is not a barrier to entry.

Regulation that was doing its job would make sure that no single company could control, for instance, a software interface. As discussed in the chapter on Creativity, an inventor of a quantum improvement in usability should get the benefit of that invention just as with any other. But it cannot become a platform for gouging. Compulsory licensing would be the obvious solution.

Another new technology that’s rapidly getting out of hand is search. Methods of information access aren’t just nice things to have. Without them, the information might as well not be there. A shredded book contains the same information as the regular variety; there’s just no way to get at it. Organizing access to information is the function of nerves and brain. Without any way to make sense of sight or sound or to remember it, an individual would be brainless. Nor would having two or three brains improve matters. If they’re separate, any given bit of information could be in the “wrong” brain unless they all worked together. They have to work as a unit to be useful. Information access is a natural monopoly if there ever was one.

The fact that search is a natural monopoly seems to have escaped too many people. Like a nervous system, without it all the information in cyberspace might just as well not be there. The usual answer is to pooh-pooh the problem, and to say anyone can come up with their own search engine. But having multiple indexers makes as much sense as having multiple water mains. It’s a duplication of effort that actually reduces value at the end.

That’s not to say that different methods can’t exist side by side. Libraries, for instance, organize information in a fundamentally different, subject-oriented way than do search engines, and that facilitates deeper approaches to the material. Left to itself, over time, the need for that approach would lead to the development of the more laborious subject-based indexes in parallel with tag-based ones. But that’s another danger with having a monopoly in the latter kind. Undue influence might not leave any parallel system to itself. To put it as a very loose analogy, word-based methods could become so dominant that mathematics hardly existed. Whole sets of essential mental tools to handle information could fall into disuse.

On the user’s side, there’s a further factor that makes search a natural monopoly. Users don’t change their habits if they can help it. (That’s why there are such heated battles among businesses over getting their icons on computer desktops. If it’s what people are used to and it’s right in front of them, the controlling market share is safe.) Instead of pretending there is no monopoly because people have the physical option to make an initially more effortful choice — something people in the aggregate have shown repeatedly they won’t do — the sustainable solution comes from facing facts. More than one indexer is wasteful, and people won’t use more than one in sufficient numbers to avoid a controlling market share. It’s a natural monopoly. So it needs to be regulated as a public utility or even be part of the government itself.

There are further considerations specifically related to search. Any inequality in access to knowledge leads to an imbalance in a wide array of benefits and disadvantages. Further, an indexer is the gateway to stored knowledge and therefore potentially exercises control over what people can learn. In other words, a search engine can suppress or promote ideas.

Consider just one small example of the disappearance at work. I wanted to remove intercalated video ads from clips on Google’s subsidiary, Youtube. But a Google search on the topic brought up nothing useful in the first three screens’ worth of results. That despite the fact that there’s a Greasemonkey script to do the job [Update, 2014-05-09, the script is no longer there]. Searches for scripts that do other things do bring up Greasemonkey on Google.

Whether or not an adblocker is disappeared down a memory hole may not be important. But the capability to make knowledge disappear is vastly important. Did Google “disappear” it on purpose? Maybe not. Maybe yes. Without access to Google’s inner workings, it’s impossible to know, and that’s the problem.

We’re in the position of not realizing what exists and what doesn’t. Something like that is far more pernicious than straight suppression. That kind of power simply cannot rest with an entity that doesn’t have to answer for its actions. Anything like that has to be under government regulation that enforces full transparency and equality of access.

(None of that even touches on the privacy concerns related to search tools, which, in private hands and without thorough legal safeguards, is another locus of power that can be abused.)

There are two points to this digression into the monopolies of the information age. One is that they should and can be prevented. They have the same anti-competitive, anti-innovative, expensive, and ultimately destabilizing effect of all monopolies. And a good regulator would be breaking them up or controlling them for the public good before they grew so powerful that nothing short of social destruction would ever dislodge them.

My second point is that monopolies may rest on other things besides capital or control of natural resources. All imbalances of market power, whether they’re due to scarce resources, scarce time, ingrained habits, or any other cause need to be recognized for what they are and regulated appropriately.

Regulations as the term is commonly used — environmental, economic, financial, health, and safety — are generally viewed as the government guaranteeing the safety, not the rights, of citizens to the extent possible. But that leads straight into a tangle of competing interests. How safe is safe? Who should be safe? Just citizens? What about foreigners who may get as much or more of the downstream consequences? How high a price are people willing to pay for how much safety?

If the justification is safety, there’s no sense that low-priced goods from countries with lax labor or environmental laws are a problem. Tariffs aren’t applied to bring them into line with sustainable practices. The regulatory climate for someone else’s economy is not seen as a safety issue. Egregious cases of slavery or child labor are frowned on, but are treated as purely ethical issues. Since immediate physical harm to consumers is not seen as part of the package, regulation takes a back seat to other concerns. Until it turns out that the pollution or CO2 or contaminants do cause a clear and present danger, and then people are angry that the situation was allowed to get so far out of hand that they were harmed.

Approaching regulations as safety issues starts at the wrong end. Sometimes safety can be defined by science, but often there are plenty of gray areas. Then regulations seem like a matter of competing interests. Safety can only be an accidental outcome of that competition unless the people at the likely receiving end of the harm have the most social power.

However, when the goal is fairness, a consistent regulatory framework is much easier to achieve. The greatest good of the greatest number, the least significant overall loss of rights, and the least harm to the greatest number is not that hard to determine in any specific instance. In a transparent system with recall elections, officials who made their decisions on a narrower basis would find themselves out of a job. And safety is a direct result, not an accidental byproduct, of seeking the least harm to the greatest number.

Consider an example. The cotton farmers of Burkina Faso cannot afford mechanization, so their crop cannot compete with US cotton. Is that a safety issue? Of course not. Cotton is their single most important export crop. If the farmers switch to opium, is that a safety issue? Sort of. If the local economy collapses, and the country becomes a haven for terrorists, that’s easy to see as a safety issue. A much worse threat, however, would be the uncontrolled spread of disease. Collapse is not just some academic talking point. The country is near the bottom of poverty lists, and who knows which crisis will be the proverbial last straw. So, once again, is bankrupting their main agricultural export a safety issue? Not right now. So nothing is done.

Is it, however, a fairness issue? Well, obviously. People should not be deprived of a livelihood because they are too poor to buy machines. There are simple things the US could do. Provide regulation so that US cotton was not causing pollution and mining land and water. The remaining difference in price could be mitigated with price supports to Burkinabe cotton. The only loss is to short term profits of US cotton farmers, and where that is a livelihood issue for smallholders assistance could be provided during the readjustment.

There may be better ways of improving justice in the situation, but my point is that even an amateur like me can see some solutions. The consequences of being fair actually benefit the US at least as much as Burkina Faso. (Soaking land in herbicide is not a Good Thing for anyone.) And twenty or thirty years down the road, people both in the US and in Burkina Faso will be safer. The things they’ll be safer from may be different — pollution in one case, social disruption in the other — but that doesn’t change the fact that safety oriented regulation has no grounds for action, but fairness oriented regulation can prevent problems.

Globalization is yet another example where regulation based on fairness facilitates sustainability. Economists like to point out that globalization can have economic benefits, and that’s true, all other things being equal. The problem is other things aren’t equal, and globalization exposes the complications created by double standards. If it applied equally to all, labor would have to be as free to move to better conditions as capital. (See this post for a longer discussion.) Given equal application of the laws, globalization couldn’t be used as a way of avoiding regulations. Tariffs would have to factor in the cost of sustainable production, and then be spent in a way that mitigated the lack of sustainability or fairness in the country (or countries) of origin. There’d be less reward for bad behavior and hence fewer expensive consequences, whether those are contaminants causing disease or social dislocation caused by low wages and lost work. Those things are only free to the companies causing the problem.

Enforcement must be just as good as the regulations or else they’re not worth the paper they’re printed on. The financial meltdown is a stark recent example showing that good regulations are not enough. Maintaining the motivation for enforcement is at least as important. In the US and in many other countries, the regulations existed to preserve the finances of the many rather than the narrow profit potential of the few. In hindsight, the element missing was any desire to enforce those regulations. (E.g. see Krugman’s blog and links therein.)

Enforcement is necessarily a task performed by officials, who are hired precisely to know enough to use foresight so that hindsight is unnecessary. That’s understood everywhere, and yet enforcement is repeatedly the weak link in the chain. That’s because the responsible officials are not really responsible. Rarely do any of them have any personal consequences for falling down on the job. That is the part that has to change.

Officials who enable catastrophe by not doing their jobs commit dereliction of duty, something that has consequences in a system emphasizing feedback and accountability. There has to be personal liability for that. People are quick to understand something when their living depends on it. (With apologies to Upton Sinclair.) The right level of personal consequences for responsible officials is not only fair, it would also provide the motivation to do the job right to begin with and avoid the problem.

For personal responsibility to be justified, the right path to take does need to be well known. I’m not suggesting officials be punished for lacking clairvoyance. I’m saying that when the conclusions of experts exceed that 90% agreement level mentioned earlier, and yet the official ignores the evidence, then they’re criminally culpable. Then a lack of action in the face of that consensus needs to be on the books as a crime, punishable by loss of assets and even jail time, depending on the magnitude of the lapse. Nor should there be any statute of limitations on the crime, because there is none on its effects. The penalties need to be heavy enough to scare officials straight, but not so heavy they’re afraid to do their jobs. Finding the right balance is another area where study is needed to find optimal answers. But regulation is a vital function of government, so it is equally vital to make sure that it’s carried out effectively. Dereliction of duty is no less a crime of state than abuse of power.

Officials who are actually motivated to do their jobs are important in a system which works for all instead of for a few. The point of fair regulation, as of fairness generally, is that avoiding problems is less traumatic than recovering from them. Prevention of problems is an essential function of regulation. Prevention takes effort ahead of time, though, when there’s still the option to be lazy, so it only happens when there’s pressure on the relevant officials. That means there have to be penalties if they don’t take necessary steps. It’s unreasonable to punish a lack of clairvoyance, and yet it’s necessary to punish officials who let a bad situation get worse because it was easier to do nothing.

In short, the government’s regulatory functions should serve to maintain a fair, sustainable environment where double standards can’t develop. Safety or low prices might be a side effect, but the purpose has to be enforcing rights.

Public Works

Contents

This is one of the few areas where the highest expression of the art of government is more than invisibility. Some of the greatest achievements of humankind come from the type of concerted action only governments can coordinate. The great pyramids of Egypt, medieval European cathedrals, and space flight were all enterprises so huge and so profitless, at least in the beginning, that they couldn’t have been carried out by any smaller entity.

People could — and have — questioned whether those projects were the best use of resources, or whether some of them were worth the awful price in suffering. The answer to the latter is, obviously, no. Where citizens have a voice, they’re not likely to agree to poverty for the sake of a big idea, so that problem won’t (?) arise. But that does leave the other questions: What is worth doing? And who decides?

There’s an irreducible minimum of things worth doing, without which a government is generally understood to be useless. The common example is defense, but on a daily level other functions essential to survival are more important. A police force and court system to resolve disputes is one such function. Commerce requires a safe and usable transportation network and reliable monetary system. In the system described here, running the selection and recall processes would be essential functions. And in a egalitarian system, both basic medical care and basic education have to be rights. It is fundamentally unfair to put a price on life and health, and equally unfair to use poverty to deprive people of the education needed to make a living.

As discussed in the chapter on Care, the definition of “basic” medical care depends on the wealth of the country. (Or of the planet, in a unified world.) In the current rich countries, such as the G20, it simply means medical care. It means everything except beauty treatments. And even those enter a gray area when deviations from normal are severe enough to cause significant social problems. On the other hand, in a country where the majority is living on a dollar a day and tax receipts are minimal, basic medical care may not be able to cover much except programs that cost a tiny fraction of the money they eventually save. That’s things like vaccinations, maternal and neonatal care, simple emergency care, pain relief, treatments against parasites, and prevention programs like providing mosquito netting, clean water, and vitamin A.

The definition of basic education likewise depends on the social context. In a pre-technological agrarian society it might be no more than six grades of school. In an industrial society, it has to include university for those who have the desire and the capacity to make use of it. The principle is that the level of education provided has to equal the level required to be eligible for good jobs, not just bottom tier jobs, in that society.

I’ve gone rather quickly from the irreducible minimum to a level of service that some in the US would consider absurdly high. Who decides what’s appropriate? I see that question as having an objective answer. We are, after all, talking about things that cost money. How much they cost and how much a government receives in taxes are pretty well-known quantities. From that it’s possible to deduce which level of taxes calls for which level of service.

The concept that a government can be held to account for a given level of service, depending on what proportion of GDP it uses in taxes, is not a common one. And the application of the concept is inevitably empirical. It is nonetheless interesting to think about the question in those terms.

As I’ve pointed out, there are several governments who have total tax receipts of about a third of GDP and provide all the basic services plus full medical, educational, retirement, and cultural benefits, as well as providing funds for research. Hence, if a country has somewhere between 30% to 40% of GDP in total tax receipts, it should be providing that level of service. If it isn’t, the citizenry is being cheated somewhere.

On a local note, yes, this does mean the US is not doing well. Total taxes here are around 28%. Japan provides all the services and benefits listed above while taking in 27% of total GDP. The low US level of services implies taxes should be lower, or services should be higher. The US does, of course, maintain a huge military which, among other things, redistributes federal tax dollars and provides some services such as education and medical care to its members. If one factors in the private cost of the tax-funded services elsewhere, US total tax rates would be over 50%. Given the gap between the US and other rich countries, the US is wasting money somewhere … .

On the other hand a poor country, which can’t fairly have much of a tax rate, might have only 5% of an already low GDP to work with. Services then would be limited to the minimums discussed earlier. Even poor governments can provide roads, police, fire protection, commercial regulation to make trade simpler, basic medicine and education. (It should go without saying, but may not, that a poor country may not have the resources to deal with disasters, and may need outside help in those cases.) The only thing that prevents some of the world’s countries from providing the basics now are corruption, incompetence, and/or the insistence of elites on burning up all available money in wars. None of those are essential or unavoidable. Fairness isn’t ruinously expensive, but its opposite is.

At any level of wealth, the receipts from fair levels of taxes dictate given levels of service. Citizens who expect more without paying for it are being unfair, and governments who provide less are no better.

There is now no widespread concept that a government is obligated to provide a given level of service for a given amount of money. Even less is there a concept that taking too much money for a given level of service is a type of crime of state. The government’s monopoly on force in a might-makes-right world means that there aren’t even theoretical limits on stealing by the state. However, when it’s the other way around and right makes might, then those limits flow logically from what is considered a fair tax level.

So far, I’ve been discussing taxes and what they buy on a per-country basis which feels artificial in a modern world where money and information flow without borders, and where we all breathe the same air. A view that considers all people equal necessarily should take a global view of what’s affordable. I haven’t discussed it that way because it seems easier to envision in the familiar categories of nations as we have them now, but there’s nothing in the principles of fair taxation and corresponding services that wouldn’t scale up to a global level.

Finally, there’s the most interesting question. In a country — or a world like ours — which is doing much better than scraping by, what awe-inspiring projects should the government undertake? How much money should be devoted to that? Who decides what’s interesting? Who decides what to spend?

Personally, I’m of the opinion that dreams are essential, and so is following them to the extent possible. I subscribe to Muslihuddin Sadi’s creed:

If of mortal goods you are bereft,

and from your slender store two loaves

alone to you are left,

sell one, and from the dole,

buy hyacinths to feed the soul.

Or, as another wise man once said, “The poor you shall always have with you.” Spend some money on the extraordinary.

So I would answer the question of whether to spend on visionary projects with a resounding “yes.” But I’m not sure whether that’s really necessary for everyone’s soul or just for mine. I’m not sure whether it’s a matter of what people need, and hence whether it should be baked into all state budgets, or whether it’s a matter of opinion that should be decided by vote. If different countries followed different paths in this regard, time would tell how critical a role this really plays.

It seems to me inescapable that countries which fund interesting projects would wind up being more innovative and interesting places. Miserly countries would then either benefit from that innovation without paying for it, which wouldn’t be fair, or become boring or backward places where fewer and fewer people wanted to live. Imbalances with unfortunate social consequences would then have to be rectified.

As for the ancillary questions of what to spend it on, and how much to spend, those are matters of opinion. Despite that, it’s not clear to me that the best way to decide them is by vote. People never would have voted to fund a space program, yet fifty years later they’ll pay any price for cellphones and they take accurate weather forecasting for granted. I and probably most people have no use for opera, and yet to others it’s one of the highest art forms.

Further, another problem is that budget instability leads to waste. Nobody would vote for waste, but voter anger can have exactly that effect. Jerking budgets around from year to year wastes astronomical sums. A good example of just how much that can cost is the tripling, quadrupling, and more of space program costs after the US Congress is done changing them every year. Voters, on the whole, are not good at the long range planning and broad perspective that large social projects require. I discuss a possible method of selection under Advanced Education. Briefly, I envision a similar system to the one suggested for other fields. A pool of proposals is vetted for validity, not value, and selection is random from among those proposals that make methodological sense. However it’s done, decisions on innovation and creativity have to be informed by innovative and creative visionaries without simultaneously allowing corrupt fools to rush in.

A fair government, like any other, has a monopoly on force, but that is not the source of its strength. The equality of all its citizens, the explicit avoidance of double standards in any sphere, the renunciation of force except to prevent abuse by force, short and direct feedback loops to keep all participants honest, and all of these things supported in a framework of laws — those are the source of its strength. The strength comes from respecting rights, and is destroyed in the moment rights get less respect than might. The biggest obstacle to reaching a true rule of law is that intuition has to be trained to understand that strength is not muscle.

So far, I can't make comments appear on archive pages. Please click on the post title or permalink to go to the post page, if you'd like to comment.

Government 1: War and Politics

Introduction

Contents

There’s irony to the fact that in a work on government, the topic itself waits to appear till somewhere in the middle. But government is a dependent variable without any chance of being functional, to say nothing of fair, if the physical and biological preconditions aren’t met. Those preconditions can be satisfied with less effort when people are savvy enough to understand where they fit in the scheme of things, but they can’t be ignored.

It’s customary, or it is now at any rate, to think of government in terms of its three branches, executive, legislative and judicial. But those are really branchlets all in one part of the tree and don’t include important aspects of the whole thing. They are all concerned with the machinery, with how to get things done, and they don’t address the why, what, or who of government.

At its root, the function of government is to coordinate essential common action for the common good. When resources are at a minimum, the function is limited to defense, which is one type of common action. In richer situations, other functions are taken on, generally at the whim of the rulers and without a coherent framework for what actually serves the common good. The priorities are less haphazard in democracies, but still don’t necessarily serve the common good. Wars of aggression come to mind as an example.

The defining characteristic of a government is said to be a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. (Parents are allowed to use force on children in all societies so far — an exception I consider wrong as I discussed in the fourth chapter — but that’s a side issue in the context of this discussion.) That force is used not only against outside threats, but also internal ones, such as criminals. An essential function of government is to protect its citizens from each other. It’s a short step from that to regulatory functions generally, to all the ways in which a government can serve to maintain the people’s rights. Economic, environmental, and safety regulations are all included here. Preventing bad actions is one type function carried out by government for the common good.

The positive functions of government are as important: the achievement of desirable goals, not merely the prevention of disaster. Some of those coordinated actions for the common good are now understood to be just as obvious a function of government as defense. Essential infrastructure is in this category, although people don’t always agree on what is essential. Ensuring basic standards of living, basic levels of health, and security in old age are also coming to be understood as something government is uniquely qualified to do. And then there are the things which fire the imagination and are a quest and an adventure rather than a necessity. These are big or not obviously profitable projects beyond the scope of smaller entities, projects such as support for basic research, for space programs, or for the arts.

Given that government has a great deal to do, it may be worth pointing out which functions it does not have. Its purpose is not to bring happiness or wealth to its citizens, only to bring the preconditions for those desirable things. And it’s certainly not to make a subset of citizens wealthy. Nor is it to make citizens healthy, only to provide the preconditions to make it easy for people to take care of their health. That’s actually a more difficult issue than the others because if health care is government-funded, then a line has to be drawn about how much self-destructive behavior to tolerate. And that runs smack into the right to do anything that doesn’t harm others. It’s a conflict I’ll discuss in the chapter on Care, near the end of the section on medicine.

So, having discussed the preconditions on which government rests, the next step is examining the machinery by which it can implement its functions. What we want from the machinery is for it to interfere with those functions as little as possible and for it to be as effortless and invisible as possible. The business of government is essentially a boring job of solving other people’s problems — or that’s what it is when abuse of power and corruption are removed from the equation. Quite clearly, we have some distance to go before achieving a silent, effortless and effective machine. Below, I’ll offer my ideas on how to get closer to that goal.

Important aspects of the machinery side of the tree which fall outside the traditional executive, legislative, and judicial zones are funding the government and overseeing it. Oversight is a particularly vital issue because the thing being overseen also has a monopoly on force. Given the willingness in enough people to accommodate anything the powerful want to do, it’s essential to counteract that call to power and to make sure that oversight retains the ability to rein in all abuses.

Instead of discussing these topics in their conceptual order above, I’ll take them in the order of their capacity to interfere with people’s lives. That will, I hope, make it easier to imagine how it might work in fact.

Force

Contents

Between groups

The bloody-minded we will always have with us, so it’s to be expected that even the most advanced human societies will always need to have some sort of defense and police forces. But their function has to be limited to small-scale threats. If an entire population flouts the law, a police force is powerless. It can only stop rare actions, not common ones. Likewise, the defense force of an equitable society would have to be targeted toward stopping occasional attacks by kooks of various kinds, not fullscale wars with equals or, worse yet, more powerful countries.

The reason for that is simple. Fair societies are not compatible with war. War is the ultimate unfairness. Its authority is might, not right. Even self-defense, in other words even a just war, is not compatible with retaining a nice sense of fair play. Wars of self-defense may be forced on a country, but that doesn’t change the facts. Justice and war are simply mutually exclusive.

No, that does not mean that an equitable society is impossible. It’s only impossible if wars are inevitable, and the evidence suggests otherwise. Looking at it from a national level, how many countries have internal wars? Some, but not all. Not even most. Somehow, this so-called inevitable state of war has been eliminated even among large groups within countries. If it can be done for some groups, it can be done for all groups.

It should go without saying, but probably doesn’t, that regressions are always possible. We could regress right back to stone-throwing cave dwellers under the right conditions. That’s not the point. The point is that war has been eliminated between some groups. How that’s done, and the huge wealth effect of doing it are obvious by now. To repeat, if it can be eliminated between some groups, it can be eliminated between all groups. It is not inevitable. Aggression isn’t about to go away, but that particular form of it known as war can and has disappeared in some cases.

Wars happen internationally because on some level enough people think they’re a better idea than the alternative. They want to retain the ability to force agreements rather than come to them. But there’s a price to pay for the method used, and it only makes practical sense if the price is not greater than the prize. Wars make no sense by any objective measure on those grounds. Their only real benefit is on a chest-thumping level, and even that works only at the very beginning, before the price starts to be paid.

For anyone who doubts my statement about price, I should mention that I’m thinking both large scale and long term. In a very narrow view, ignoring most of the costs, one could claim that it’s possible to win something in a war. Take the view down a notch from international to national, and it becomes clear how flawed it is. It’s as if one were thinking on the same level as a Somali warlord. If Somalia had not had a generation with no government, and hadn’t spent the time in the grip of warring gangs, anybody on earth (except maybe a Somali warlord) would agree they’d be much richer and better off in every way. Ironically, even the warlords themselves would be better off. They wouldn’t have to spend a fortune on armed guards, for starters. And yet, unable to think of a way of life different from the hellhole they’re in now, they keep shooting in the hope of winning something in a wasteland they’re reducing to nothing.

That, on an international scale, is where our national minds are. That, on an international scale is the price we also pay. What we’re losing for the planet is the difference between Sweden and Somalia. When the vision of what we’re losing becomes obvious to enough people, and when the pain of not having it becomes big enough, that’s when we’ll decide that an international body to resolve disputes is a better idea than the idiotic notion of trial by ordeal. Then it’ll be obvious what’s the better choice, even if trial by law does mean losing the occasional case. After all, that can happen in trial by ordeal too, but with much more devastation.

So, no, I don’t think that the incompatibility between fairness and war is the end for fair societies. I think it’s ultimately the end for war.

The beginnings of that evolution seem to be happening already. War is becoming less and less of an option between some countries. Even the concept of war between Austria and Italy, or Japan and France, is just laughable. They wouldn’t do it. They’d negotiate each others’ ears off, but they’d come to some resolution without killing each other.

That’s the future. An extrapolation of the past is not.

The fact that the US is closer to the past than the future doesn’t change the trajectory. Likewise with the other large powers, China, Russia, India, Brazil. They all have further to go than anyone would like, but that only means regressions are possible. It still doesn’t change the direction of the path. And even the US seems to feel the need for UN permission before marching into other countries and blowing them up. That’s something I don’t remember seeing ever before. It’s a sign of a potential sea change, if they don’t zig backwards again. The next step would be to actually stop blowing people up. We’ll see if they zag forward and take it.

If violent methods are not an option as a final solution to disputes, then the only alternatives when ordinary channels aren’t working are nonviolent ones. That is not as utopian as the people who fancy themselves hard-headed realists assume. A tally by Karatnycky and Ackerman (2005) (pdf) of the 67 conflicts that took place from 1973 to 2002 indicates that mass nonmilitary action was likelier to overturn a government and — even more interesting — much likelier to lead to lasting and democratic governments afterward. (69% vs 8%, and 23% with some intermediate level of civic involvement.) Armed conflicts, in contrast, tended to result simply in new dictatorships, when they succeeded at all. It is easy to argue with their exact definitions of what is free and how the struggles took place. But short of coming up with an ad hoc argument for every instance, the broader pattern of the effectiveness of nonviolence in both getting results and in getting desirable results is clear.

As the article points out, some of the initially freedom-enhancing outcomes were later subverted. Zunes et al. (1999) cite one notable example in Iran:

Once in power, the Islamic regime proved to abandon its nonviolent methodology, particularly in the period after its dramatic shift to the right in the spring of 1981. However, there was clear recognition of the utilitarian advantages of nonviolent methods by the Islamic opposition while out of power which made their victory possible.

The interesting point here is not that regression is to be expected when nonviolence is used as a tool by those with no commitment to its principles. The interesting thing is that its effectiveness is sufficiently superior that it’s used by such people.

That effectiveness makes little sense intuitively, but that’s because intuition tells us we’re more afraid of being killed than having someone wave a placard at us. Fear tells us that placard-waving does nothing, but violence will get results. But that intuition is wrong. Fear isn’t actually what lends strength to an uprising. What counts is how many people are in it and how much they’re willing to lose. The larger that side is, the more brutal the repression has to be to succeed, until it passes a line where too few soldiers are able to stomach their orders.

That pattern is repeated over and over again, but each time it’s treated as a joke before it succeeds, and if it succeeds it’s assumed to be an exception. The facts become eclipsed by the inability to understand them. The hardheaded realists can go on ignoring reality.

The faulty emotional intuition on nonviolence leads to other mistakes besides incorrect assessments of the chances of future success. It results in blindness to its effects in the present and the past as well. As they say in the news business, if it bleeds, it leads. The more violence, the more “story.” We hear much more about armed struggle, even if it kills people in ones and twos, than we do about movements by thousands that kill nobody. How many people are aware of nonviolent Druze opposition to Israeli occupation in the Golan Heights versus the awareness of armed Palestinian opposition? How many even know that there is a strong nonviolent Palestinian opposition? The same emotional orientation toward threats means that nonviolence is edited out of history and flushed down the memory hole. History, at least the kind non-historians get at school, winds up being about battles. The result is to confirm our faulty intuition, to forget the real forces that caused change, and to fix the impression that violence is decisive when in fact it is merely spectacular.

Admittedly, the more brutal the starting point, the less likely nonviolence is to succeed. The people whose struggle awes me the most, the Tibetans, are up against one of the largest and most ruthless opponents on the planet. Even though their nonviolence is right, it’s no guarantee of the happy ending. But — and this is the important point — the more brutal the basic conditions, the less chance that violence can succeed. The less likely it is that anything can succeed in pulling people back from a tightening spiral of self-destruction. Places like the Congo come to mind. The more equitable a society is to start with, the better nonviolent methods will work.

“Common sense” may make it hard to see the facts of the effectiveness of nonviolence, but even common sense knows that ethical treatment is likelier to lead to ethical outcomes than brutality. The fact that armed conflict is incompatible with justice is not a disadvantage to a fair society, so long as it remembers that violence is the hallmark of illegitimacy. The state itself must view the application of violence as fundamentally illegitimate and therefore use its own monopoly on force only in highly codified ways. An analogy is the blanket prohibition against knifing other people, except in the specific set of circumstances that require surgery. I’ll discuss the distinction a bit more below. A refusal to use violence is a clear standard to apply, and it gives the state that applies it an inoculation against one whole route to subversion. When violence is understood to be a hallmark of illegitimacy, then it can’t be used as a tool to take power no matter how good the cause supposedly is, and no matter whether the abuse comes from the state or smaller groups.

Another objection runs along the lines of “What are you going to do about Hitlers in this world of yours?” “What about the communists?” Or “the Americans” if you’re a communist. “What about invasions?” What, in short, about force in the hands of bad guys? If one takes the question down a level, it’s easier to understand what’s being asked. In a neighborhood, for instance, a police force is a more effective response to criminals than citizens all individually arming themselves. The real answer to force in the hands of bad guys is to take it out of their hands in the first place. If a gang is forming, the effective response is not to wait for attack but to prevent it.

On a local level, the effectiveness of police over individual action is obvious. On an international level, it seems laughable because the thugs have power. But that’s common sense playing us false again. Brute force threats are not inevitable. They’re human actions, not natural forces. They’re symptoms of a breakdown in the larger body politic. The best way to deal with them is to avoid the breakdown to begin with, which is not as impossible as it might seem after the fact. The currently peaceful wealthy nations show that dispute resolution by international agreement is possible and they show how much there is to gain by it.

That indicates that objections about the impossibility of using international norms to handle “bad guys” are really something else. An answer that actually solves the problem is to strengthen international institutions until the thugs can’t operate, just as good policing prevents neighborhood crime. However, when people make that objection, international cooperation is the one solution they won’t entertain. That suggests they’re not looking for a solution. Otherwise they’d be willing to consider anything that works. They’re really insisting on continued thuggery, using the excuse that so-and-so did it first.

At its most basic level, the argument about the need to wage war on “bad guys” is built on the flawed logic of assuming the threat, and then insisting there’s only one way to deal with it. The Somali warlord model of international relations is not our only choice.

Force against criminals

Contents

Just as war is incompatible with fairness, so is any other application of force where might makes right. Therefore force is justifiable only to the extent that it serves what’s right. It’s similar to the paradox of requiring equal tolerance for everyone: the only view that can’t be tolerated is intolerance. Force can’t be used by anyone: it can only be used against someone using it.

Force can be applied only to the extent of protecting everyone’s rights, including the person causing the problem, to the extent compatible with the primary purpose of stopping them from doing violence. The state can use only as much force as is needed to stop criminal behavior and no more.

Because the state does have the monopoly on force, it is more important to guard against its abuse in state hands than any others. Crimes of state are worse than crimes of individuals. Not only do people take their tone from the powerful, but they’re also too ready to overlook bad actions by them. So the corrupting influence of abuse is much greater when done by those in power, and it is much more necessary to be vigilant against people’s willingness to ignore it. An event such as the one where an unarmed, wheelchair-bound man was tasered would be considered a national disgrace in a society that cared about rights. It would be considered a national emergency in a society that cared about rights if people saw tasering as the expected result of insufficient deference to a uniform. That fascist attitude has become surprisingly common in the U.S.

The exercise of state power carries responsibilities as well as limits. When criminals are imprisoned, the state becomes responsible for them. That’s generally recognized, but somehow the obvious implications can be missed. Not only must the state not hurt them, it has taken on the responsibility for preventing others from hurting them as well. The jailers can’t mistreat prisoners. That much is obvious. But neither can people condone the torture of prisoners by other prisoners. The dominant US view that rape in prisons is nobody’s concern is another national emergency. Proper care of prisoners is expensive. People who don’t want the expense can’t, in justice, hold prisoners.

The death penalty is another practice that cannot be defended in a just context. Its justification is supposed to be that is the ultimate deterrent, but a whole mountain of research has shown by now that, if anything, crimes punishable by death are more common in countries with death penalties than without. If the irrevocable act of killing someone serves no legitimate goal, then it can have no place in a just society.

Another problem is the final nature of the punishment. It presumes infallibility in the judicial system, which is ludicrous on the face of it. Fallibility has been shown time and again, and tallied in yet another mountain of research. Executing the innocent is something that simply cannot happen in a society with ambitions of justice.

But perhaps the most insidious effect of having a death penalty is what it says, even more than what it does. The most powerful entity is saying that killing those who defy it is a valid response. And it’s saying that killing them solves something. The state, of course, makes a major point of following due procedure before the end, but that’s not the impressive part of the lesson. People take their tone from those in power, and for those already inclined to step on others’ rights, the due process part isn’t important. What they hear is that even the highest, the mightiest, and the most respectable think that killing is all right. They think it solves something. If it’s true for them, it becomes true for everyone. No amount of lecturing that the “right” to kill works only for judges will convince criminals who want to believe otherwise. By any reasoning, ethical, practical, or psychological, the death penalty is lethal to a fair society.

Decision-making

Contents

Voting

The bad news is that democracy does not seem to work as a way of making sustainable decisions. The evidence is everywhere. The planet is demonstrably spiraling toward disaster through pollution, overpopulation, and tinpot warring dictators, and no democracy anywhere has been able to muster a proportional response. The most advanced have mustered some response, but not enough by any measure. A high failing grade is still a failure.

Given that democracy is the least-bad system out there, that is grim news indeed. But the good news is that we haven’t really tried democracy yet.

As currently practiced, it’s defined as universal suffrage. (Except where it isn’t. Saudi Arabia is not, for some reason, subject to massive boycotts for being anti-democratic even though it enforces a huge system of apartheid.) But defining democracy down to mere voting is a sign of demoralization about achieving the real thing. Democracy is a great deal more than voting. It’s supposed to be a way of expressing the will of the people, and voting is just a means to that end. For that matter, the will of the people is considered a good thing because it’s assumed to be the straightest route to the greatest good of the greatest number. There’s a mass of assumptions to unpack.

Assumption 1: the greatest good of the greatest number is a desirable goal. So far, so good. I think everybody agrees on that (but maybe only because we’re assuming it’s bound to include us).

Assumption 2: Most people will vote in their own self-interest and in the aggregate that will produce the desired result. The greatest good of the greatest number is the outcome of majority rule with no further effort needed. Assumption 2 has not been working so well for us. Possibly that has to do with the further assumption, Assumption 2a, that most people will apply enlightened self-interest. Enlightenment of any kind is in short supply.

The other problem is Assumption 2b, which is that majority rule will produce the best results for everyone, not just for the majority. There is nothing to protect the interests of minorities with whom the majority is not in sympathy.

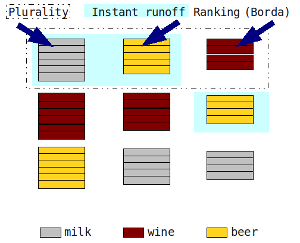

Assumption 3: Tallying the votes will show what the majority wants. This is such a simple idea it seems more like a statement of fact, and yet reality indicates that it’s the easiest part of the process to rig. Most of the time, people don’t know what they want. Or, to be more precise, they know what they want — a peaceful, happy, interesting life for themselves and their children — but they’re not so sure how to get there. So a few ads can often be enough to tell them, and get them voting for something which may be a route to happiness, but only for the person who funded the ads. Besides the existential difficulty of figuring out what one wants, there’s also a morass of technical pitfalls. Redrawing voting districts can find a majority for almost any point of view desired. Different ways of counting the votes can hand elections to small minorities. Expressing the will of the majority, even if that is a good idea, is far from simple.